Surfing is not soccer. It’s not basketball, nor football. For better or worse, it’s one of those obscure pursuits that is far more singular than collective—a deeply personal experience, unique to the individual.

Yet despite that singularity in the water, on land there’s a much more collective dynamic—and it can be spotted a mile away. It’s like a secret society of those with gills and those without. As my friend Joey Lombardo likes to say, the surf community is a tribal one.

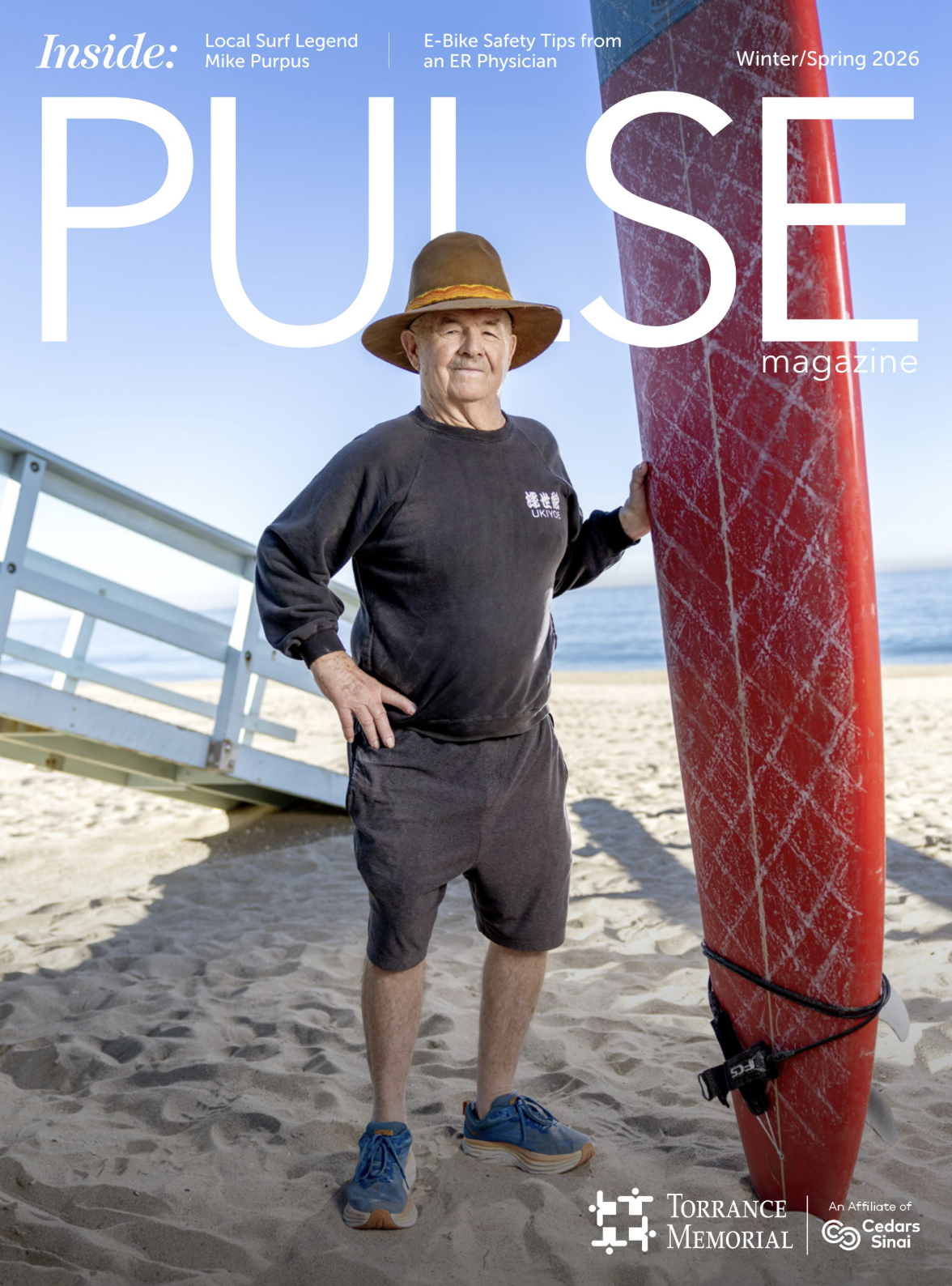

Those with the gills will already know this man, but many of you may not—Mike Purpus. Born and raised in Hermosa Beach, he is one of the world’s gifts to surfing. He grew up during a unique era, right between the longboard transition and the shortboard revolution. Unconventional and magnetic, his surfing mirrored his larger-than-life personality. On land and in many tribal circles, a cosmic warrior of sorts.

His résumé includes a second-place finish at the 1972 Makaha International Championships; competing in the World Surfing Championships in 1968, 1970, and 1972; a five-time invitee to the Duke Kahanamoku Invitational; and being the first star on the Hermosa Beach Surfers’ Walk of Fame. To this day, he remains the oldest competitor in the South Bay Boardriders Surf Contest Series.

But upon closer examination, there’s something a little different about Purp.

As we prepared for this story, he walked me through his Redondo home, showing me trophies, achievements, photos, and memorabilia. Yet there was something else in the room—something unseen. Something that hung in the air and settled over the dusty trophies and faded nylon carpet.

As he chatted about this story or that, this trophy or that achievement, there was a magnetism to him. It was layered with humor. That humor was layered with joy. And that joy was layered with something magnetic and hard to put a finger on—rooted in service. It communicated something along the lines of: You’re my friend. Welcome to my home. I’m so stoked you’re here.

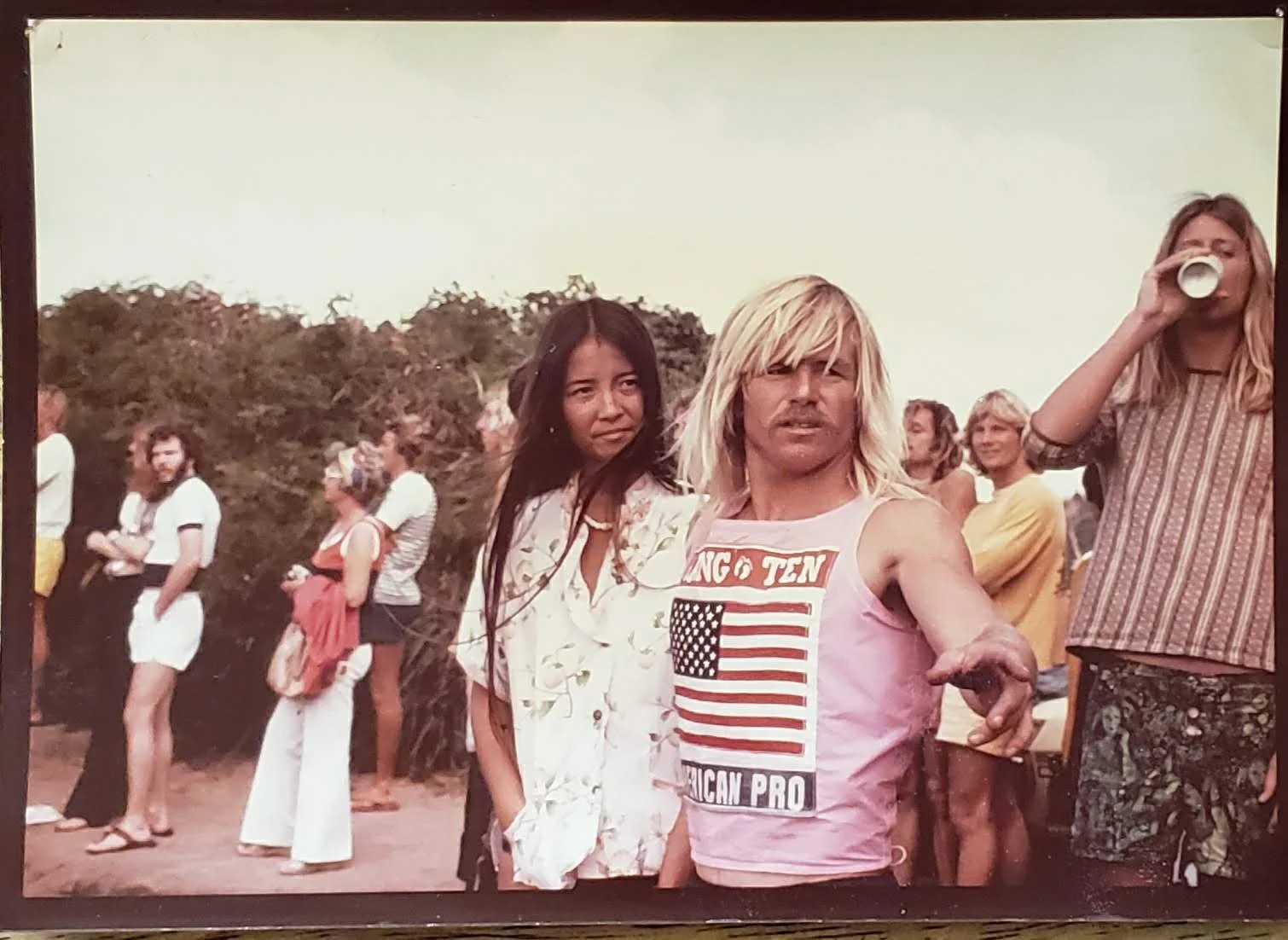

Mike Purpus & Freinds

Did you know that across various tribal communities—from Hawaiian to Tongan, Zulu, Navajo, and beyond—chiefs have traditionally led through service? In return, the tribe takes care of the chief, allowing the chief to continue to take care of the tribe. This mutual responsibility creates long-term stability and places leadership at the center of the communal well-being.

Fun fact: Purp hasn’t had a driver’s license since 1980. So how does he get where he needs to go? Nonchalantly, he says, “I have friends.”

Today, his good friend Steve Littrell gives him a ride wherever Purp needs to go—doctor appointments, grocery store runs, you name it. Steve is the wheels. And it should be said: Steve lives in Lakewood, not around the corner.

Did you know that many societies and tribal communities throughout history didn’t collapse due to outside enemies or sudden disasters? They collapsed because leadership at the top stopped working. When chiefs became status-driven rather than stewardship-driven—turning power into something symbolic and competitive—it created internal conflict, often leading to abandonment, social destabilization, and ultimately, population collapse.

Purp chooses people. And the people choose Purp. It’s been that way his whole life. As his good friend Dan Merkel says, “Mike freely gives others the aloha spirit.” Alo means presence, face, or shared space. Hā means breath or life force. Together, aloha means “the sharing of breath”—a recognition of mutual existence and connection. That is exactly what Mike has and gives away freely.

And I’m pretty sure that’s what I felt in Purp’s home that day. You know it when you feel it. A commodity that’s becoming harder and harder to come by in the lone-wolf, entrepreneurial, influencer economy we find ourselves in. Money can’t buy it. But boy oh boy do people want it. Just a little unsure how to access it.

Purp stewards it freely… and in return, the tribe takes care of it’s chief.

Thank you, Mike Purpus, for your aloha. For the stories. For the laughs. For the radical performance in and out of the water—but most of all, for your stewardship of the things money can’t buy. Your aloha is woven into the very fabric of the South Bay’s communal identity, and for that, the tribe thanks you.